An intense meditation retreat was the occasion for my first panic attack. The triggers have been various, but in each episode there has been an overwhelming need to escape, yet nowhere to go, and a feeling of being completely alone.

Mindfulness therapies and techniques are currently lauded as a panacea for emotional distress, yet stories circulate of practitioners running into dangerous psychological difficulties through meditation. “An underlying psychosis†is the explanation rolled out by those with an interest in preserving the reputation of mindfulness. Meditation veterans tend to the view that run-ins with psychosis are part of the territory, more likely to be encountered the longer we explore, regardless of our baseline nuttiness.

Perhaps all spiritual practices are both a cure and a poison; they can dramatically improve mental health, but also they put it at risk.

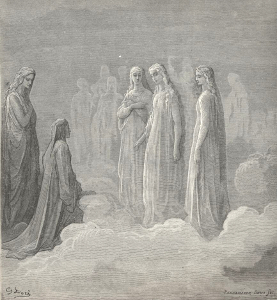

Dante, be thou my guide

Dante’s Divine Comedy is a text operating on many levels, but fundamentally a poetic description of three spiritual realms. In Hell, the damned suffer torments from which they can never escape. Every moment is a desperate longing for relief that can never be realised. The damned are isolated in their suffering for eternity. During a panic attack, I know how this feels.

In Heaven, the blessed are perfectly fulfilled. Even though they are situated at various distances from God, their wills are aligned with God’s. The soul in Heaven furthest from God is as fulfilled as the closest, because all rejoice in divine will (“True Willâ€) as their own. I know that paradoxically complete fulfilment of non-dual emptiness, which is just my own paltry experience of it.

Purgatory speaks most to the spiritual practitioner. Here, souls endure torments not dissimilar from Hell, but do so willingly. Suffering operates as a penance for sins, which gains the souls entrance to Heaven. Indeed, Purgatory guarantees Heaven; it is simply a matter of time and effort.

Maybe it’s significant how Purgatory has no explicit basis in Christian scripture, but was a doctrine developed later. Given Heaven and Hell, Purgatory is a means of transition; less of an end-point, more of a methodology.

Dispelling the stench of Sunday school

To prevent anti-religious hackles from being raised, we can read these allegorical realms not in terms of “should†but “isâ€. The compulsion upon souls in each realm is imposed not from outside but arises from its own nature; a soul in Purgatory does not “have to†burn off its sin, but might be said to be in Purgatory if and when it does. If the word “sin†is difficult to tolerate, then “psychological issues†or “karma†will do instead.

As meditators, we endure long hours of discomfort, frustration and despair; countless dark nights in return for luminous glimpses. No one forces us to do so. The ups and downs of my spiritual practice are due to factors personal to me.

These “sins†are my own psychological issues; in actuality, I am never lost and abandoned, but something in my nature makes it seem so. The fault lies in me, even though it is not necessarily my fault. It is simply that I am the fault, although – ultimately – there really never was one. If Heaven is free of sin, then Hell is where we live out its full effects. And if something different happens in Purgatory, it’s because here we confront our issues willingly and with awareness. Spiritual practice is the atonement of sin. Whereas some atone because they think God demands it, the rest of us do it just because we know it works.

Famously, at the entrance to Hell is written: “Abandon Hope All Who Enterâ€. The only difference between Purgatory and Hell is the fact of an exit, and with the hope this offers in Purgatory all the horror is vanquished. What is hope, other than knowing that what we must confront will one day change?

Psychiatrists, awaken!

Russell Razzaque is a psychiatrist who experienced awakening after taking up meditation. He noticed significant parallels between his own experience and that of his patients. In Breaking Down Is Waking Up he formulates a model of psychological suffering as an inversion of awakening. Whereas spiritual practice gradually dismantles the ego, in mental illness the ego reacts to psychological stress by expanding, but eventually cracks appear as the ego collapses under its own weight: “as it was not a process that was sought, planned or gradually worked towards – with any awareness of a reality beyond the ego – the experience becomes a frightening and distressing one†(Razzaque 2014: 142-3).

In the same week I was reading Razzaque, I attended a talk by Daniel Hadjiandreou, a psychologist who (admitting a tendency to take things to extremes) practised for seven hours straight a meditation technique supposed to be practised for only one minute per day. The result was a traumatic dissolving of reality that necessitated a difficult process of recovery. His talk provided a number of simple, psychological techniques to help anyone affected by experiences of “unshared realityâ€.

I highly recommend Razzaque’s book; it is a radical re-visioning of psychiatry in relation to spirituality, and is likely to be of practical use to anyone undergoing psychological difficulties on a spiritual path. But I do not share his view of mindfulness and meditation as necessarily beneficial. Whereas, for Razzaque, meditation was a gateway into Purgatory, for Hadjiandreou – initially, at least – it was an entrance into Hell.

Razzaque suggests a continuum between enlightenment and psychosis; Dante offers a model of three distinct realms. The advantage of Dante is an explanation for how practice is evidently not the sole determinant of experience. Mindfulness is commonly presented as universally helpful, and next in line (it seems) are psychological treatments combined with psychedelics. Yet for every person whom these assist through Purgatory and into Heaven, some will be led straight into Hell.

Forgive us our trespasses

Someone with a tendency to take things to extremes practices meditation. Discovering another reality, the current one seems totally false, and must be utterly meaningless…

Someone who grew up in an over-protective environment undergoes ego dissolution. It feels like complete abandonment and eternal separation…

Our own psychological issues filter the experience of what lies beyond ego. What comes from inside the ego can seem to be what is “realâ€, in which case there is no way out from it and suddenly we are in Hell. The purgatorial pledge to confront our sins has been swept away, and, with it, hope.

Whatever our practice, sometimes it plunges us deeper into Hell. Dante’s model reminds us of the importance of reference points. Maps are helpful: knowing where you are and where you are headed can sustain the purgatorial sense of an exit, the consoling knowledge that, one day, this too will pass. Also helpful are guides: through Hell and Purgatory Dante has Virgil by his side; but for navigating Heaven, only Beatrice will do. Different guides offer different perspectives, and it needs to be recognised what those perspectives are.

Psychotherapy has proved helpful for uncovering my “sinsâ€, the issues that distort my understanding and plunge me into Hell. My therapist seems to have little appreciation of spiritual practice. She questions my self-exploration outside the therapeutic context. But she has helped me through difficult times, and I have found her insights grounding. She is more of a Virgil to me than a Beatrice; for spiritual guidance, I turn elsewhere.

What Dante offers is an unwelcome illustration of an unfashionable truth: that spiritual practice alone is insufficient. We must also atone for our sins, in the sense of recognising our own psychological stuff, a means of preventing us from mistaking it for reality. As long as we can do this, hope is preserved, and the exit into Heaven guaranteed.

References

Dante Alighieri (2013). The Divine Comedy, translated by Clive James. London: Picador.

Razzaque, Russell (2014). Breaking Down is Waking Up: Can Psychological Suffering be a Spiritual Gateway? London: Watkins.